As far as we can tell Alan Greenspan was right only a single time after he took the helm of the Fed in August 1987. That was when he said flat out that under the modern banking and financial system it is damn near impossible to measure “money”, let alone track it by the week and month and make monetary policy based on pegging the growth rate of the money supply.

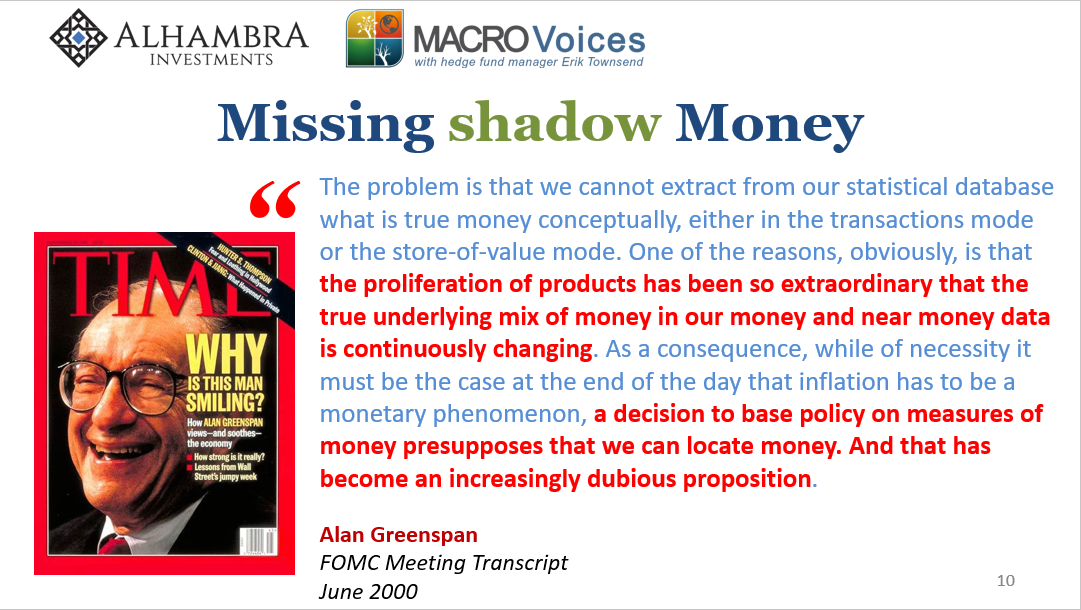

Jeff Snider has highlighted this point well in the graphic insert below, but the second red bolded sentence cannot be repeated often enough. Said the Maestro,

A decision to base policy on measures of money presupposes that we can locate money. And that has become an increasingly dubious proposition.

Note that these words were spoken on June 28, 2000 in the very inner sanctum of the Eccles Building. They were recorded word for word in the FOMC meeting transcript and released with a ten year lag so as not to disturb the public with knowledge of what the nation’s central bankers really thought at a moment which was pregnant with monetary and financial significance—or any other time for that matter.

That is, during the 1990s the Greenspan Fed had fostered the monumental tech and dotcom bubble, inflating the NASDAQ-100 egregiously—-from an index level of 600 during March 1996 to 4700 on March 27, 2000.

Needless to say, that Fake Money based 675% gain was not destined to last. In fact, by April 14, just 14 trading days later, the index had plunged by 32% to 3207, and then kept on keeping on ever lower until it finally touched bottom at 800 on October 8, 2002.

So those who rode the bubble from start to finish ended up where they started in inflation adjusted dollars, while the speculators who jumped on along the way and the mullets who came aboard at the tippy-top lost their lunch—-85% of it from the March 27, 2000 peak.

Needless to say, honest capital markets do not make the kind of violent round trip shown below in less than six years.

That can only happen when the equity markets are contaminated with bad money; and when false credit and liquidity fostered by the central bank have overwhelmed the market’s normal mechanisms of fact based price discovery, two-way trading and financial discipline owing to proper weighting of the risk of loss and cost of position carry.

In June 2000, you did not need to be clairvoyant about the remaining months of the cliff dive. It was absolutely clear at the time that the stock market was rife with speculative mania, and that the miracles of the computer age or no, nothing could possibly justify the 675% gain in the NASDAQ-100 index over the previous 48 months.

The market in June 2000 was a big fat June Bug begging to encounter a windshield.

So Greenspan’s core recognition that the era of Milton Friedman’s rule based fiat money growth was over and done should have given great pause to the denizens of the Eccles Building.

In fact, it was either a call to go back to anchoring the dollar to gold from which it had been severed by Tricky Dick back in August 1971 at Uncle Milton’s urgings, or at least urgently suggestive of the need for an extended sabbatical on “policy” making at the Fed until its members contemplated the paradox of conducting monetary policy without the medium of Money.

Yet if there was ever a road not taken, this was the one. With virtually no deliberations at all, the Greenspan Fed simply abandoned Money and wholeheartedly embraced Economy. So doing, they fundamentally transformed the nation’s central bank from an overseer of Money and the banking system in which it was embedded into a Keynesian monetary central planner with a writ across the entire financial system and the highways and byways of main street America.

Stated differently, at that ripe juncture of history the Fed actually had a chance to declare victory and essentially go out of business. That’s because if there had ever been a need for a “central bank”, the matter perturbing the Maestro as above quoted on June 28, 2000 was actually evidence that one was no longer much needed.

That is, the rise of technology and innovation in banking practices symbolized by the “sweep account” in the early 1990s meant that the ever resourceful operators of the banking system had found a way to essentially eliminate the need for reserves on checking accounts. They did this by using technology to cycle non-interest bearing checking accounts during the daylights hours to interest-bearing time deposits at night.

Presto, the 10% reserve requirement for checking deposits at the daily measurement time was eliminated, thereby sharply diminishing the need for commercial banks to hold vault cash or reserve deposits at their district Federal Reserve bank in order to comply with the age-old regulatory regime on fractional reserve banking.

Needless to say, what the modern central bank does is print currency (via what are essentially sub-contract orders for cash to the US treasury department) under their state granted monopoly on legal tender; and create bank “reserves” out of thin air via open market operations under their statutory authority to manage the banking system.

The is often referred to as “high powered money” as opposed to actual M1 money consisting of hand-to-hand currency in circulation and checkable deposit money at commercial banks.

But if suddenly required bank reserves and vault cash were in far lower demand in the banking system, exactly what were the printers of hand-to-hand currency and bank reserves domiciled in the Eccles Building to do with their time and statutory authorities?

Indeed, just in the previous six years, fundamental trends in the banking system were making it abundantly clear that central banking in the historic sense of superintending Money was going the way of the doo-doo bird. To wit, the sum of vault cash and required reserves at the Fed in the banking system in January 1994 had been $98.6 billion, representing 2.94% of the banking system’s total liabilities of $3.35 trillion.

By contrast, as of June 2000, the sum of vault cash and bank reserves had dropped to $82.8 billion, even as total banking system liabilities had soared by 68% to $5.64 trillion. This meant that the reserve ratio in the banking system had been cut in half to just 1.47% in only six years.

Moreover, that was merely the acceleration of a trend that had been long underway. Back in 1973, vault cash and required reserved had totaled $39 billion, which represented 6.0% of total bank liabilities at $646 billion.

The reason that required reserves were disappearing relative to the liability base of the banking system, of course, is that the mix of bank liabilities was steadily moving away from reservable checking money to other deposit and funding forms (i.e. repo and commercial paper). In turn, that shift was owing to the fact that depositors wanted to earn interest on their money and competition and technology were making its ever more convenient and efficient for banks to meet these demands.

In fact, there was really no need for traditional central banking by the year 2000 because its main product— hand-to-hand currency—-was largely disappearing from the system owing to the convenience of payment by credit cards and checks. Without various state-driven incentives for the use of currency in the illegal underground—-evasion of high taxes, illegal drugs and other social crimes and international smuggling—there is actually no reason why it couldn’t have provided as a service in the form of commercial bank issued money as it had been until the Fed’s taxed it out of business after the civil war.

Likewise, there were always plenty of excess reserves—at a price or market clearing interest rate—-sloshing around the banking system for the main form of modern money, checkable deposits. Indeed, in June 2000 required reserves against checkable deposit totaled only $38 billion or 0.6% of total bank liabilities and 0.37% of GDP at $10.3 trillion.

In short, financial evolution and technology had more or less eliminated the alleged need for traditional central banking. If there was ever a moment when the once-upon-a-time goldbug who had been put in charge of the central bank by our last goldbug president, Ronald Reagan, could have pointed that out and sought to bend policy toward a return to sound money, that was the moment.

But June 2000 is also the point at which Uncle Milton Friedman’s baleful influence steered history in the exact wrong direction. That’s because Friedman had been a closet Keynesian all along, and had erroneously claimed that GDP growth and prosperity were a function of money supply growth, and that the change rate of the latter, in turn, could be managed to nearly the decimal point by the rate of growth in high-powered money ladled out by the Fed.

In fact, that was nonsense all along, and was heavily influenced by a completely erroneous interpretation of the causes of the Great Depression. But suffice it to say here, the velocity of money is far from constant, meaning that you can’t steer GDP growth with lock-step money growth, nor is the money multiplier constant, which means you can’t steer money growth to the decimal point, either.

Yet it was the false Friedmanite equation that Money drives Economy that led Greenspan to his fatal error. As we will explicate further in Part 2, he simply jumped the shark of Money and led the Fed straight into the business of directly managing Economy through the crude instrument of pegging the money market rate of interest.

At length, of course, pegging the money market rate was a horrible error because over time it was driven closer and closer to the zero bound by the eager-beaver Keynesians who steadily took over the Fed, thereby also steadily increasing the incentive for carry trade speculation on Wall Street.

Still, the first sentence of the post-meeting release from June 28, 2000 tells you all you need to know. The money market rate was 6.5% and the monumental bubble of the 1990s was being purged from the system.

At totally different world would have emerged on the other side if it had been held at that level and Greenspan had not jumped the shark during the next four years and driven the money market rate to 1.0%, and to the credit housing and credit bubble that emerged therefrom.

The Federal Open Market Committee at its meeting today decided to maintain the existing stance of monetary policy, keeping its target for the federal funds rate at 6-1/2 percent.